Look, you shouldn’t believe everything you read on social media. But these days … the internet might be on to something.

In recent years, there’s been a viral trend of people online noticing that … we don’t seem to be aging the way we used to.

For instance, this is a 35-year-old man today:

And this was one in the 1940s:

And while this is a 50-year-old woman in 2020:

This was a 50-year-old woman in 1984:

All of which has led the experts to one important question: What the hell happened?

[OPENING SEQUENCE]

The key to understanding how the aging process has changed for Americans lies with one man…

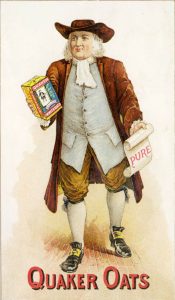

The Quaker Oats Guy:

No, not that one. He’s undead and has roamed the forests of Pennsylvania for centuries.

This Quaker Oats guy:

This is the late actor Wilford Brimley, and there are two important things to know about him. First, he may be the only actor in history remembered primarily for how he said one word: [several clips of Brimley saying “diabetes”]

Second, Wilford Brimley has become a kind of Rosetta Stone for the aging process.

Here’s why: When Brimley appeared in the 1985 film Cocoon, he was just shy of 51 years old…

…and yet he looked like this:

And people on the internet have started noticing that these days many people at the same age … do not look like that.

This inspired the creation of “The Brimley Line,” a meme in which the internet comes together to point out when other celebrities are the same age as Wilford Brimley was in Cocoon. And, well … it kind of proves their point.

Gwyneth Paltrow? Past the Brimley line.

Idris Elba? Past the Brimley line.

Cameron Diaz? Past the Brimley line.

Paul Rudd? Past the Brimley line — but, also, this man has looked the same for 30 years and it’s clearly sorcery.

Now, there are obviously some big asterisks here. For one thing, celebrities have more resources than most people to combat the aging process. And, for another, Wilford Brimley was one of those guys who just looked old.

But, those caveats aside, there’s also a lot of evidence to suggest that there’s something real going on here. We are actually slowing down the aging process.

A 2018 study that looked at “biological age” — the actual amount of measurable aging in our bodies, as opposed to our age on the calendar — found that women over 60 seemed 3 1/2 years younger in 2010 than they had in 1988. For men over 60, it was nearly 4 1/2 years.i

And the quality of those years is getting better too. Another study found that between 2008 and 2017, the proportion of seniors who had functional limitations — things like difficulty walking or climbing stairs — fell by about 14 percent.ii The proportion who had trouble with daily tasks like dressing or bathing went down by over 20 percent.iii

So, what’s going on here?

It’s not that we suddenly discovered a fountain of youth. In fact, it’s kind of the opposite. In recent decades, a lot of not-necessarily-glamorous scientific work has made slow and steady progress across many different areas. And when you add them all up, you get radical changes in human longevity and well-being.

Think about how far we’ve come in only the space of a few generations.

In just the 100 years or so that we’ve had antibiotics we’ve added 23 years to the average lifespan.iv

Between 1950 and 2017, the death rate of Americans from flu and pneumonia — ailments most people no longer even think of as life-threatening — fell by about 70 percent.v

And this progress has continued into the 21st century. Between 1999 and 2020, for instance, the rate of Americans dying from heart attacks fell by more than half.vi

All of which is great, but … it still doesn’t quite explain why the appearance of aging seems to have changed. After all, past generations also had people who lived to advanced ages. But none of them looked like Christopher Plummer did when he was pushing 90.

On this front, a big part of the story is changes to our lifestyles. In 1954, 45 percent of Americans were smoking.vii By 2023, that number was 12 percent. viii And the relationship between smoking and visible signs of aging is so clear that even sober, scholarly papers will tell you that it makes you look “ugly and old.”ix

Ok … sober, scholarly, and slightly b****y papers.

Another surprisingly important factor: sunscreen. In recent decades, substantially more Americans have been using it.x Why does that matter? Because as much as 80 percent of the skin’s visible signs of aging come not from the simple fact of getting older but from exposure to the ultraviolet light that sunscreen protects against.xi

One other factor that often goes overlooked: In the past, way more people had jobs that involved grueling physical labor that could accelerate the signs of aging. But as the economy has shifted to less physically taxing types of work, our stressors have tended to move from the physical to the mental.xii

So, congratulations, America: Now we all look great … in our therapist’s office.

But, when you think about it … that’s actually a pretty good deal. The reason that Americans now have so much more time to focus on their mental health or their emotional well-being is because they’re no longer consumed by the more immediate threats that previous generations faced.

After all, it wasn’t that long ago that heart attacks killed around half of their victims within a few days. Today, more than 90 percent of people survive.xiii

And it wasn’t that much longer before that — the year 1900 — when the average American life expectancy was 47. By 1940, it had jumped to 63 — the biggest increase in our history. One of the biggest reasons why? Because we did something as seemingly basic as cleaning up the water supplies in our cities.xiv

Bottom line: We’ve got it better than we may realize. We’re living lives that previous generations could never have dreamed of: longer, healthier, and yes, even better-looking. And it’s all thanks to the work of scientists and researchers, many of whose names we’ll never know.

Unless you’re Paul Rudd — in which case it’s all thanks to a medieval spell book.

SOURCE(S)

- “Is 60 the New 50? Examining Changes in Biological Age Over the Past Two Decades” (Morgan Levine and Eileen Crimmins) — Demography

- “Temporal Trends (From 2008 to 2017) in Functional Limitations and Limitations in Activities of Daily Living: Findings From a Nationally Representative Sample of 5.4 Million Older Americans” (Esme Fuller-Thomson, Jason Ferreirinha, and Katherine Marie Ahlin) — International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

- Ibid.

- “Antibiotics: Past, Present and Future” (Matthew Hutchings, Andrew Truman, and Barrie Wilkinson) — Current Opinion in Microbiology

- Age-Adjusted Death Rates for Selected Causes of Death, by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: United States, Selected Years 1950–2017 — Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Heart Attack Deaths Drop over Past Two Decades — American College of Cardiology

- “U.S. Cigarette Smoking Rate Steady Near Historical Low” (Jeffrey Jones) — Gallup

- Ibid.

- “Does Cigarette Smoking Make You Ugly and Old?” (Deborah Grady and Virginia Ernster) — American Journal of Epidemiology

- Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health — National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

- “Ultraviolet Radiation, Aging and the Skin: Prevention of Damage by Topical Camp Manipulation” (Alexandra Amaro-Ortiz, Betty Yan, and John D’Orazio) — Molecules

- “We Used To Look Older” (Jonathan Jarry) — McGill University Office for Science and Safety

- How Heart Attacks Became Less Deadly — Harvard Medical School

- “The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The 20th Century United States” (David Cutler and Grant Miller) — Demography